Cache Architecture¶

Introduction¶

In addition to being an HTTP proxy, Apache Traffic Server™ is also an HTTP cache. Traffic Server can cache any octet stream, although it currently supports only those octet streams delivered by the HTTP protocol. When such a stream is cached (along with the HTTP protocol headers) it is termed an object in the cache. Each object is identified by a globally unique value called a cache key.

The purpose of this document is to describe the basic structure and implementation details of the Traffic Server cache. Configuration of the cache will be discussed only to the extent needed to understand the internal mechanisms. This document will be useful primarily to Traffic Server developers working on the Traffic Server codebase or plugins for Traffic Server. It is assumed the reader is already familiar with the Administrator’s Guide and specifically with HTTP Proxy Caching and Proxy Cache Configuration along with the associated configuration files.

Unfortunately, the internal terminology is not particularly consistent, so this document will frequently use terms in different ways than they are used in the code in an attempt to create some consistency.

Cache Layout¶

The following sections describe how persistent cache data is structured. Traffic Server treats its persistent storage as an undifferentiated collection of bytes, assuming no other structure to it. In particular, it does not use the file system of the host operating system. If a file is used it is used only to mark out the set of bytes to be used.

Cache storage¶

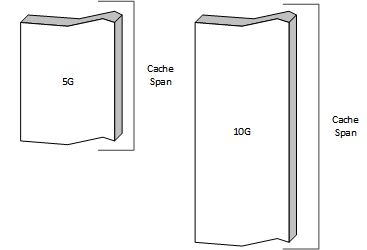

The raw storage for the Traffic Server cache is configured in storage.config. Each

line in the file defines a cache span which is treated as a uniform

persistent store.

Two cache spans¶

This storage is organized into a set of administrative units which are called cache volumes. These are defined in volume.config. Cache volumes can be assigned

different properties in hosting.config.

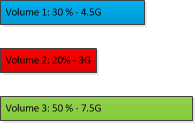

Cache volumes can be defined by a percentage of the total storage or as an absolute amount of storage. By default, each cache volume is spread across all of the cache spans for robustness. The intersection of a cache volume and a cache span is a cache stripe. Each cache span is divided into cache stripes and each cache volume is a collection of those stripes. Every cache stripe is in a single cache span and part of a single cache volume.

If the cache volumes for the example cache spans were defined as:

Then the actual layout would look like:

Cache stripes are the fundamental unit of cache for the implementation. A

cached object is stored entirely in a single stripe, and therefore in a single

cache span. Objects are never split across cache spans or volumes. Objects are

assigned to a stripe (and in turn to a cache volume) automatically based on a

hash of the URI used to retrieve the object from the origin server. It

is possible to configure this to a limited extent in hosting.config,

which supports content from specific hosts or domain to be stored on specific

cache volumes. It’s also possible to control which cache spans (and hence,

which cache stripes) are contained in a specific cache volume.

The layout and structure of the cache spans, the cache volumes, and the cache

stripes that compose them are derived entirely from storage.config and

cache.config and is recomputed from scratch when the

traffic_server is started. Therefore, any change to those files can

(and almost always will) invalidate the existing cache in its entirety.

Span Structure¶

Each cache span is marked at the front with a span header of type DiskHeader. Each span is

divided in to span blocks. These can be thought of similarly to normal disk partitions, marking

out blocks of storage. Span blocks can vary in size, subject only to being a multiple of the

volume block size which is currently 128MB and, of course, being no larger than the span. The

relationship between a span block and a cache stripe is the same as between a disk partition and a

file system. A cache stripe is structured data contained in a span block and always occupies the

entire span block.

Stripe Structure¶

Traffic Server treats the storage associated with a cache stripe as an undifferentiated span of bytes. Internally each stripe is treated almost entirely independently. The data structures described in this section are duplicated for each stripe.

Internally the term volume is used for these stripes and implemented primarily

in StripeSM. What a user thinks of as a volume (and what this document

calls a cache volume) is represented by CacheVol.

Note

Stripe assignment must be done before working with an object because the directory is local to the stripe. Any cached objects for which the stripe assignment is changed are effectively lost as their directory data will not be found in the new stripe.

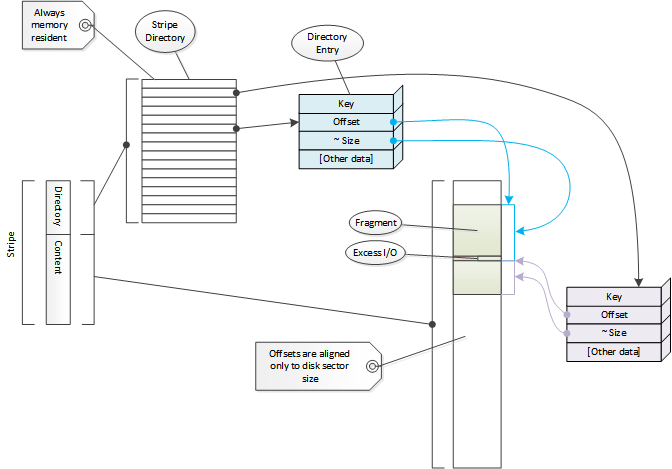

Cache Directory¶

Content in a stripe is tracked via a directory. Each element of the directory

is a directory entry and is represented by Dir. Each entry

refers to a chunk of contiguous storage in the cache. These are referred to

variously as fragments, segments, docs, documents, and a few other

things. This document will use the term fragment as that is the most common

reference in the code. The term Doc (for Doc) will be used to

refer to the header data for a fragment. Overall, the directory is treated as a

hash with the cache ID as the key. See

directory probing for how the cache ID is used

to locate a directory entry. The cache ID is in turn computed from a

cache key which by default is the URL of the content.

The directory is used as a memory resident structure, which means a directory entry is as small as possible (currently 10 bytes). This forces some compromises on the data that can be stored there. On the other hand this means that most cache misses do not require disk I/O, which has a large performance benefit.

The directory is always fully sized; once a stripe is initialized the directory size is fixed and never changed. This size is related (roughly linearly) to the size of the stripe. It is for this reason the memory footprint of Traffic Server depends strongly on the size of the disk cache. Because the directory size does not change, neither does this memory requirement, so Traffic Server does not consume more memory as more content is stored in the cache. If there is enough memory to run Traffic Server with an empty cache there is enough to run it with a full cache.

The resident size of the directory for a cache volume is generally <0.2% of the volume size. The exact memory allocated for the directory of a volume can be seen if traffic_server is run with the ‘cache_init’ debug tag enabled.

Each entry stores an offset in the stripe and a size. The size stored in the directory entry is an approximate size which is at least as big as the actual data in the fragment. Exact size data is stored in the fragment header on disk.

Note

Data in HTTP headers cannot be examined without disk I/O. This includes the original URL for the object. The cache key is not stored explicitly and therefore cannot be reliably retrieved.

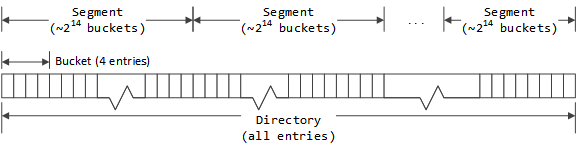

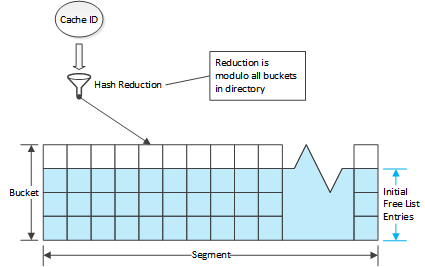

The directory is a hash table that uses chaining for collision resolution. Because each entry is small they are used directly as the list header of the hash bucket.

Chaining is implemented by imposing grouping structures on the entries in a

directory. The first level grouping is a directory bucket. This is a

fixed number (currently 4, defined as DIR_DEPTH) of entries. This serves to

define the basic hash buckets with the first entry in each cache bucket serving

as the root of the hash bucket.

Note

The term bucket is used in the code to mean both the conceptual bucket for hashing and for a structural grouping mechanism in the directory. These will be qualified as needed to distinguish them. The unqualified term bucket is almost always used to mean the structural grouping in the directory.

Directory buckets are grouped in to segments. All segments in a stripe have the same number of buckets. The number of segments in a stripe is chosen so that each segment has as many buckets as possible without exceeding 65,535 (216-1) entries in a segment.

Each directory entry has a previous and next index value which is used to link entries in the same segment. Because no segment has more than 65,535 entries, 16 bits suffices for storing the index values. The stripe header contains an array of entry indices which are used as the roots of entry free lists, one for each segment. Active entries are stored via the bucket structure. When a stripe is initialized the first entry in each bucket is zeroed (marked unused) and all other entries are put in the corresponding segment free list in the stripe header. This means the first entry of each directory bucket is used as the root of a hash bucket and is therefore marked unused rather than being put a free list. The other entries in the directory bucket are preferred for adding to the corresponding hash bucket but this is not required. The segment free lists are initialized such that the extra bucket entries are added in order; all the seconds, then the thirds, then the fourths. Because the free lists are FIFOs, this means extra entries will be selected from the fourth entries across all the buckets first, then the thirds, etc. When allocating a new directory entry in a bucket the entries are searched from first to last, which maximizes bucket locality (that is, cache IDs that map to the same hash bucket will also tend to use the same directory bucket).

Entries are removed from the free list when used and returned when no longer in use. When a fragment needs to be put in to the directory the cache ID is used to locate a hash bucket (which also determines the segment and directory bucket). If the first entry in the directory bucket is marked unused, it is used. Otherwise, the other entries in the bucket are searched and if any are on the free list, that entry is used. If none are available then the first entry on the segment free list is used. This entry is attached to the hash bucket via the same next and previous indices used for the free list so that it can be found when doing a lookup of a cache ID.

Storage Layout¶

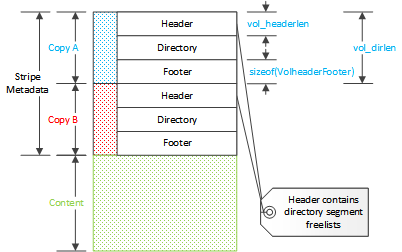

The storage layout is the stripe metadata followed by cached content. The

metadata consists of three parts: the stripe header, the directory, and the

stripe footer. The metadata is stored twice. The header and the footer are

instances of StripeHeaderFooter. This is a stub structure which can

have a trailing variable sized array. This array is used as the segment free

list roots in the directory. Each contains the segment index of the first

element of the free list for the segment. The footer is a copy of the header

without the segment free lists. This makes the size of the header dependent on

the directory but not that of the footer.

Each stripe has several values that describe its basic layout:

- skip

The start of stripe data. This represents either space reserved at the start of a physical device to avoid problems with the host operating system, or an offset representing use of space in the cache span by other stripes.

- start

The offset for the start of the content, after the stripe metadata.

- length

Total number of bytes in the stripe.

Stripe::len.- data length

Total number of blocks in the stripe available for content storage.

Stripe::data_blocks.

Note

Great care must be taken with sizes and lengths in the cache code because there are at least three different metrics (bytes, cache blocks, store blocks) used in various places.

The header for a stripe is a variably sized instance of StripeHeaderFooter.

The variable trailing section contains the head indices of the directory entry

free lists for the segments.

The trailing StripeHeaderFooter::freelist array overlays the disk storage with

an entry for every segment, even though the array is declared to have length 1.

Each free list entry is a 16 bit value that is the index of the first directory entry

in the free list for that segment. E.g. freelist[4] is the index of the

directory entry in segment 4 that is the first directory entry in the free list for

segment 4. The rest of the free list is chained from that directory entry.

The segment freelist is attached only to the header - the trailer, although of the same class, does not have a freelist and is always a fixed size.

The total size of the directory (the number of entries)

is computed by taking the size of the cache stripe and dividing by the

average object size. The directory always consumes this amount of memory which

has the effect that if cache size is increased so is the memory requirement for

Traffic Server. The average object size defaults to 8000 bytes but can be configured using

proxy.config.cache.min_average_object_size. Increasing the average

object size will reduce the memory footprint of the directory at the expense of

reducing the number of distinct objects that can be stored in the cache.

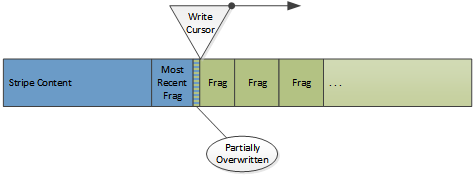

The content area stores the actual objects and is used as a circular buffer where new objects overwrite the least recently cached objects. The location in a stripe where new cache data is written is called the write cursor. This means that objects can be de facto evicted from cache even if they have not expired if the data is overwritten by the write cursor. If an object is overwritten this is not detected at that time and the directory is not updated. Instead it will be noted if the object is accessed in the future and the disk read of the fragment fails.

The write cursor and documents in the cache.¶

Note

Cache data on disk is never updated.

This is a key thing to keep in mind. What appear to be updates (such as doing a refresh on stale content and getting back a 304) are actually new copies of data being written at the write cursor. The originals are left as “dead” space which will be consumed when the write cursor arrives at that disk location. Once the stripe directory is updated (in memory) the original fragment in the cache is effectively destroyed. This is the general space management technique used in other cases as well. If an object needs to removed from cache, only the directory needs to be changed. No other work (and particularly, no disk I/O) needs to be done.

Object Structure¶

Objects are stored as two types of data: metadata and content data. Metadata is all the data about the object and the content and includes the HTTP headers. The content data is the content of the object, the octet stream delivered to the client as the object.

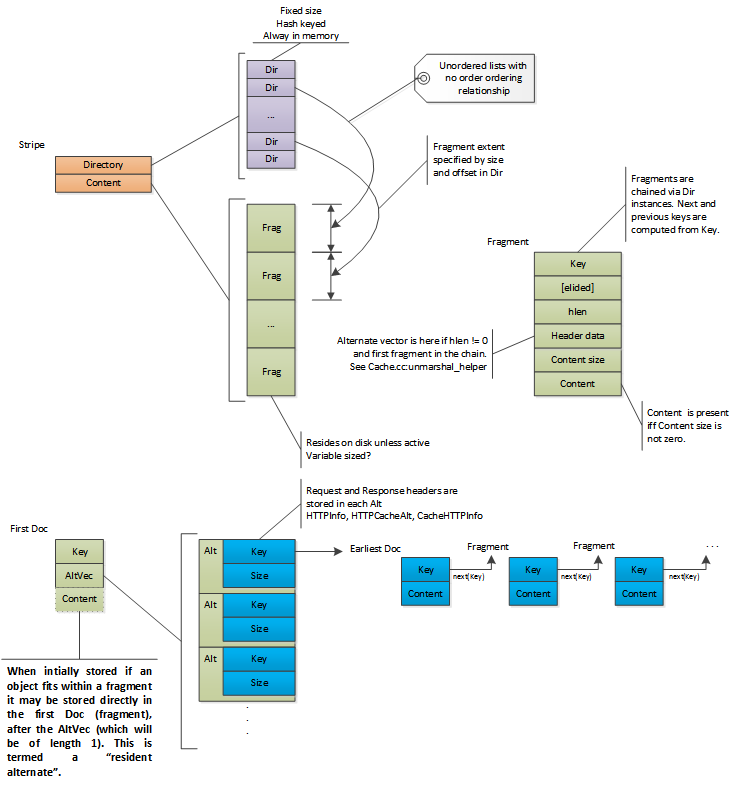

Objects are rooted in a Doc structure stored in the cache.

Doc serves as the header data for a cache fragment and is

contained at the start of every fragment. The first fragment for an object is

termed the First Doc and always contains the object metadata. Any

operation on the object will read this fragment first. The fragment is located

by converting the cache key for the object to a cache ID and

then doing a lookup for a directory entry with that key. The directory

entry has the offset and approximate size of the first fragment which is then

read from the disk. This fragment will contain the request header and response

along with overall object properties (such as content length).

Traffic Server supports varying content for objects. These are called alternates. All metadata for all alternates is stored in the first fragment including the set of alternates and the HTTP headers for them. This enables “alternate selection” to be done after the first Doc is read from disk. An object that has more than one alternate will have the alternate content stored separately from the first fragment. For objects with only one alternate the content may or may not be in the same (first) fragment as the metadata. Each separate alternate content is allocated a directory entry and the key for that entry is stored in the first fragment metadata.

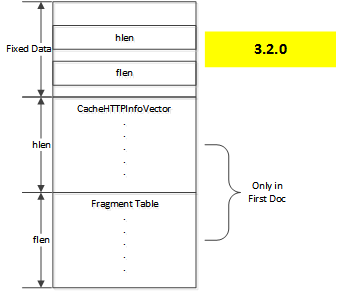

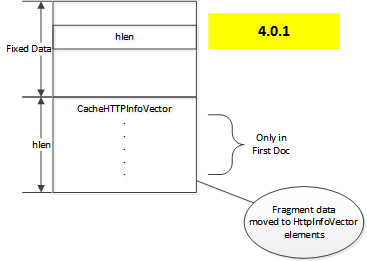

Prior to version 4.0.1, the header data was stored in the

CacheHTTPInfoVector class which was marshaled to a variable length

area of the on disk image, followed by information about additional fragments

if needed to store the object.

Doc layout 3.2.0¶

This had the problem that with only one fragment table it could not be reliable

for objects with more than one alternate [1]. Therefore, the

fragment data was moved from being a separate variable length section of the

metadata to being directly incorporated in to the CacheHTTPInfoVector,

yielding a layout of the following form.

Doc layout 4.0.1¶

Each element in the vector contains for each alternate, in addition to the HTTP headers and the fragment table (if any), a cache key. This cache key identifies a directory entry that is referred to as the earliest Doc. This is the location where the content for the alternate begins.

When the object is first cached, it will have a single alternate and that will

be stored (if not too large) in first Doc. This is termed a resident alternate

in the code. This can only happen on the initial store of the object. If the

metadata is updated (such as a 304 response to an If-Modified-Since

request) then unless the object is small, the object data will be left in the

original fragment and a new fragment written as the first fragment, making the

alternate non-resident. Small is defined as a length smaller than

proxy.config.cache.alt_rewrite_max_size.

Note

The CacheHTTPInfoVector is stored only in the first Doc.

Subsequent Doc instances for the object, including the earliest Doc,

should have an hlen of zero and if not, it is ignored.

Large objects are split in to multiple fragments when written to the cache. This

is indicated by a total document length that is longer than the content in

first Doc or an earliest Doc. In such a case a fragment offset table is

stored. This contains the byte offset in the object content of the first byte

of content data for each fragment past the first (as the offset for the first

is always zero). This allows range requests to be serviced much more

efficiently for large objects, as intermediate fragments that do not contain

data in the range can be skipped. The last fragment in the sequence is detected

by the fragment size and offset reaching the end of the total size of the

object, there is no explicit end mark. Each fragment is computationally chained

from the previous in that the cache key for fragment N is computed by:

key_for_N_plus_one = next_key(key_for_N);

Where next_key is a global function that deterministically computes a new

cache key from an existing cache key.

Objects with multiple fragments are laid out such that the data fragments

(including the earliest Doc) are written first and the first Doc is

written last. When read from disk, both the first and earliest Doc are

validated (tested to ensure that they haven’t been overwritten by the write

cursor) to verify that the entire document is present on disk (as they bookend

the other fragments - the write cursor cannot overwrite them without overwriting

at least one of the verified Doc instances). Note that while the fragments

of a single object are ordered they are not necessarily contiguous, as data from

different objects are interleaved as the data arrives in Traffic Server.

Multi-alternate and multi-fragment object storage¶

Documents which are pinned into the cache must not be overwritten so they are evacuated from in front of the write cursor. Each fragment is read and rewritten. There is a special lookup mechanism for objects that are being evacuated so that they can be found in memory rather than the potentially unreliable disk regions. The cache scans ahead of the write cursor to discover pinned objects as there is a dead zone immediately before the write cursor from which data cannot be evacuated. Evacuated data is read from disk and placed in the write queue and written as its turn comes up.

Objects can only be pinned via cache.config and while

proxy.config.cache.permit.pinning is set to non-zero (it is zero by

default). Objects which are in use when the write cursor is near use the same

underlying evacuation mechanism but are handled automatically and not via the

explicit pinned bit in Dir.

Additional Notes¶

Some general observations on the data structures.

Cyclone buffer¶

Because the cache is a cyclone cache, objects are not preserved for an indefinite time. Even if the object is not stale it can be overwritten as the cache cycles through its volume. Marking an object as pinned preserves the object through the passage of the write cursor but this is done by copying the object across the gap, in effect re-storing it in the cache. Pinning large objects or a large number objects can lead to excessive disk activity. The original purpose of pinning was for small, frequently used objects explicitly marked by the administrator.

This means the purpose of expiration data on objects is simply to prevent them from being served to clients. They are not in the standard sense deleted or cleaned up. The space can’t be immediately reclaimed in any event, because writing only happens at the write cursor. Deleting an object consists only of removing the directory entries in the volume directory which suffices to (eventually) free the space and render the document inaccessible.

Historically, the cache was designed this way because web content was relatively small and not particularly consistent. The design also provided high performance and low consistency requirements. There are no fragmentation issues for the storage, and both cache misses and object deletions require no disk I/O. It does not deal particularly well with long term storage of large objects. See the Volume Tagging appendix for details on some work in this area.

Disk Failure¶

The cache is designed to be relatively resistant to disk failures. Because each

storage unit in each cache volume is mostly independent, the

loss of a disk simply means that the corresponding StripeSM instances

(one per cache volume that uses the storage unit) becomes unusable. The primary

issue is updating the volume assignment table to both preserve assignments for

objects on still operational volumes while distributing the assignments from the

failed disk to those operational volumes. This mostly done in:

AIO_Callback_handler::handle_disk_failure

Restoring a disk to active duty is a more difficult task. Changing the volume assignment of a cache key renders any currently cached data inaccessible. This is not a problem when a disk has failed, but is a bit trickier to decide which cached objects are to be de facto evicted if a new storage unit is added to a running system. The mechanism for this, if any, is still under investigation.

Implementation Details¶

Stripe Directory¶

The in memory volume directory entries are described below.

-

class Dir¶

Defined in iocore/cache/P_CacheDir.h.

Name

Type

Use

offset

unsigned int:24

Offset of first byte of metadata (volume relative)

big

unsigned in:2

Size multiplier

size

unsigned int:6

Size

tag

unsigned int:12

Partial key (fast collision check)

phase

unsigned int:1

Phase of the

Doc(for dir valid check)head

unsigned int:1

Flag: first fragment in an object

pinned

unsigned int:1

Flag: document is pinned

token

unsigned int:1

Flag: Unknown

next

unsigned int:16

Segment local index of next entry.

offset_high

unsigned int:16

High order offset bits

The stripe directory is an array of Dir instances. Each entry refers to

a span in the volume which contains a cached object. Because every object in

the cache has at least one directory entry this data has been made as small

as possible.

The offset value is the starting byte of the object in the volume. It is 40 bits long, split between the offset (lower 24 bits) and offset_high (upper 16 bits) members. Note that since there is a directory for every storage unit in a cache volume, this is the offset in to the slice of a storage unit attached to that volume.

The size and big values are used to calculate the approximate size of

the fragment which contains the object. This value is used as the number of

bytes to read from storage at the offset value. The exact size is contained

in the object metadata in Doc which is consulted once the read

has completed. For this reason, the approximate size needs to be at least as

large as the actual size but can be larger, at the cost of reading the

extraneous bytes.

The computation of the approximate size of the fragment is defined as:

( *size* + 1 ) * 2 ^ ( CACHE_BLOCK_SHIFT + 3 * *big* )

Where CACHE_BLOCK_SHIFT is the bit width of the size of a basic cache

block (9, corresponding to a sector size of 512). Therefore the value with

current defines is:

( *size* + 1 ) * 2 ^ (9 + 3 * *big*)

Because big is 2 bits, the values for the multiplier of size are:

big

Multiplier

Maximum Size

0

512 (2^9)

32768 (2^15)

1

4096 (2^12)

262144 (2^18)

2

32768 (2^15)

2097152 (2^21)

3

262144 (2^18)

16777216 (2^24)

Note also that size is effectively offset by one, so a value of 0 indicates a single unit of the multiplier.

The target fragment size can set with the records.yaml value

proxy.config.cache.target_fragment_size.

This value should be chosen so that it is a multiple of a

cache entry multiplier. It is not necessary to make it a

power of two [2]. Larger fragments increase I/O efficiency but

lead to more wasted space. The default size (1M, 2^20) is a reasonable choice

in most circumstances, although in very specific cases there can be benefit from

tuning this parameter. Traffic Server imposes an internal maximum of a 4,194,232 bytes,

which is 4M (2^22), less the size of a struct Doc. In practice,

the largest reasonable target fragment size is 4M - 262,144 = 3,932,160.

When a fragment is stored to disk, the size data in the cache index entry is set to the finest granularity permitted by the size of the fragment. To determine this, consult the cache entry multiplier table and find the smallest maximum size that is at least as large as the fragment. That will indicate the value of big selected and therefore the granularity of the approximate size. That represents the largest possible amount of wasted disk I/O when the fragment is read from disk.

The set of index entries for a volume are grouped in to segments. The number of segments for an index is selected so that there are as few segments as possible such that no segment has more than 2^16 entries. Intra-segment references can therefore use a 16 bit value to refer to any other entry in the segment.

Index entries in a segment are grouped buckets, each

of DIR_DEPTH (currently 4) entries. These are handled in the standard hash

table manner, giving somewhat less than 2^14 buckets per segment.

Directory Probing¶

Directory probing is the locating of a specific directory entry in the

stripe directory based on a cache ID. This is handled primarily by the

function dir_probe(). This is passed the cache ID (key), a

stripe (d), and a last collision (last_collision). The last of

these is an in and out parameter, updated as useful during the probe.

Given an ID, the top half (64 bits) is used as a segment

index, taken modulo the number of segments in the directory. The bottom half is

used as a bucket index, taken modulo the number of buckets

per segment. The last_collision value is used to mark the last matching

entry returned by dir_probe().

After computing the appropriate bucket, the entries in that bucket are searched to find a match. In this case a match is detected by comparison of the bottom 12 bits of the cache ID (the cache tag). The search starts at the base entry for the bucket and then proceeds via the linked list of entries from that first entry. If a tag match is found and there is no collision then that entry is returned and last_collision is updated to that entry. If collision is set and if it isn’t the current match, the search continues down the linked list, otherwise collision is cleared and the search continues.

The effect of this is that matches are skipped until the last returned match (last_collision) is found, after which the next match (if any) is returned. If the search falls off the end of the linked list, then a miss result is returned (if no last collision), otherwise the probe is restarted after clearing the collision on the presumption that the entry for the collision has been removed from the bucket. This can lead to repeats among the returned values but guarantees that no valid entry will be skipped.

Last collision can therefore be used to restart a probe at a later time. This is important because the match returned may not be the actual object. Although the hashing of the cache ID to a bucket and the tag matching is unlikely to create false positives, it is possible. When a fragment is read the full cache ID is available and checked and if wrong, that read can be discarded and the next possible match from the directory found because the cache virtual connection tracks the last collision value.

Cache Operations¶

Cache activity starts after the HTTP request header has been parsed and remapped. Tunneled transactions do not interact with the cache because the headers are never parsed.

To understand the logic we must introduce the term cache valid which means

something that is directly related to an object that is valid to be put in the

cache (e.g. a DELETE which refers to a URL that is cache valid but cannot

be cached itself). This is important because Traffic Server computes cache validity

several times during a transaction and only performs cache operations for cache

valid results. The criteria used changes during the course of the transaction

as well. This is done to avoid the cost of cache activity for objects that

cannot be in the cache.

The three basic cache operations are: lookup, read, and write. We will take deleting entries as a special case of writing where only the volume directory is updated.

After the client request header is parsed and is determined to be potentially cacheable, a cache lookup is done. If successful, a cache read is attempted. If either the lookup or the read fails and the content is considered cacheable then a cache write is attempted.

Cacheability¶

The first thing done with a request with respect to cache is to determine whether it is potentially a valid object for the cache. After initial parsing and remapping, this check is done primarily to detect a negative result, as it allows further cache processing to be skipped. It will not be put in to the cache, nor will a cache lookup be performed. There are a number of prerequisites along with configuration options to change them. Additional cacheability checks are done later in the process, when more is known about the transaction (such as plugin operations and the origin server response). Those checks are described as appropriate in the sections on the relevant operations.

The set of things which can affect cacheability are:

Built in constraints.

Settings in

records.yaml.Settings in

cache.config.Plugin operations.

The initial internal checks, along with their records.yaml

overrides [3], are done in HttpTransact::is_request_cache_lookupable.

The checks that are done are:

- Cacheable Method

The request must be one of

GET,HEAD,POST,DELETE,PUT.See

HttpTransact::is_method_cache_lookupable().- Dynamic URL

Traffic Server tries to avoid caching dynamic content because it’s dynamic. A URL is considered dynamic if:

It is not

HTTPorHTTPS,Has query parameters,

Ends in

asp,Has

cgiin the path.This check can be disabled by setting a non-zero value for

proxy.config.http.cache.cache_urls_that_look_dynamic.In addition if a TTL is set for rule that matches in

cache.configthen this check is not done.- Range Request

Cache valid only if

proxy.config.http.cache.range.lookupinrecords.yamlis non-zero. This does not mean the range request can be cached, only that it might be satisfiable from the cache. In addition,proxy.config.http.cache.range.writecan be set to try to force a write on a range request. This probably has little value at the moment, but if for example the origin server ignores theRange:header, this option can allow for the response to be cached. It is disabled by default, for best performance.

A plugin can call TSHttpTxnReqCacheableSet() to force the request to

be viewed as cache valid.

Cache Lookup¶

If the initial request is not determined to be cache invalid then a lookup is

done. Cache lookup determines if an object is in the cache and if so, where it

is located. In some cases the lookup proceeds to read the first Doc from

disk to verify the object is still present in the cache.

The basic steps to a cache lookup are:

The cache key is computed.

This is normally computed using the request URL but it can be overridden by a plugin . The cache index string is not stored, as it is presumed computable from the client request headers.

The cache stripe is determined (based on the cache key).

The cache key is used as a hash key in to an array of

StripeSMinstances byCache::key_to_stripe(). The construction and arrangement of this array is the essence of how volumes are assigned.The cache stripe directory is probed using the index key computed from the cache key.

Various other lookaside directories are checked as well, such as the aggregation buffer.

If the directory entry is found the first

Docis read from disk and checked for validity.This is done in

CacheVC::openReadStartHead()orCacheVC::openReadStartEarliest()which are tightly coupled methods.

If the lookup succeeds, then a more detailed directory entry (struct

OpenDir) is created. Note that the directory probe includes a check

for an already extant OpenDir which, if found, is returned without

additional work.

Cache Read¶

Cache read starts after a successful cache lookup. At this point the first

Doc has been loaded in to memory and can be consulted for additional

information. This will always contain the HTTP headers for all

alternates of the object.

At this point an alternate for the object is selected. This is done by comparing

the client request to the stored response headers, but it can be controlled by a

plugin using TS_HTTP_ALT_SELECT_HOOK.

The content can now be checked to see if it is stale by calculating the freshness of the object. This is essentially checking how old the object is by looking at the headers and possibly other metadata (note that the headers can’t be checked until we’ve selected an alternate).

Most of this work is done in HttpTransact::what_is_document_freshness.

First, the TTL (time to live) value, which can be set in cache.config,

is checked if the request matches the configuration file line. This is done

based on when the object was placed in the cache, not on any data in the

headers.

Next, an internal flag (needs-revalidate-once) is checked if the

cache.config value revalidate-after is not set, and if set the

object is marked stale.

After these checks the object age is calculated by HttpTransactHeaders::calculate_document_age.

and then any configured fuzzing is applied. The limits to this age based on

available data is calculated by HttpTransact::calculate_document_freshness_limit.

How this age is used is determined by the records.yaml setting for

proxy.config.http.cache.when_to_revalidate. If this is 0 then the

built calculations are used which compare the freshness limits with document

age, modified by any of the client supplied cache control values (max-age,

min-fresh, max-stale) unless explicitly overridden in

cache.config.

If the object is not stale then it is served to the client. If it is stale, the

client request may be changed to an If Modified Since request to

revalidate.

The request is served using a standard virtual connection tunnel (HttpTunnel)

with the CacheVC acting as the producer and the client NetVC

acting as the sink. If the request is a range request this can be modified with

a transform to select the appropriate parts of the object or, if the request

contains a single range, it can use the range acceleration.

Range acceleration is done by consulting a fragment offset table attached to

the earliest Doc which contains offsets for all fragments past the first.

This allows loading the fragment containing the first requested byte immediately

rather than performing reads on the intermediate fragments.

Cache Write¶

Writing to the cache is handled by an instance of the class CacheVC.

This is a virtual connection which receives data and writes it to cache, acting

as a sink. For a standard transaction data transfers between virtual connections

(VConns) are handled by HttpTunnel. Writing to the cache is done

by attaching a CacheVC instance as a tunnel consumer. It therefore operates

in parallel with the virtual connection that transfers data to the client. The

data does not flow to the cache and then to the client, it is split and goes

both directions in parallel. This avoids any data synchronization issues between

the two.

While each CacheVC handles its transactions independently, they do interact

at the volume level as each CacheVC makes calls to

the volume object to write its data to the volume content. The CacheVC

accumulates data internally until either the transaction is complete or the

amount of data to write exceeds the target fragment size. In the former

case the entire object is submitted to the volume to be written. In the latter

case, a target fragment size amount of data is submitted and the CacheVC

continues to operate on subsequent data. The volume in turn places these write

requests in an holding area called the aggregation buffer.

For objects under the target fragment size, there is no consideration of order,

the object is simply written to the volume content. For larger objects, the

earliest Doc is written first and the first Doc written last. This

provides some detection ability should the object be overwritten. Because of

the nature of the write cursor no fragment after the first fragment (in the

earliest Doc) can be overwritten without also overwriting that first

fragment (since we know at the time the object was finalized in the cache the

write cursor was at the position of the first Doc).

Note

It is the responsibility of the CacheVC to not submit writes that exceed

the target fragment size.

Update¶

Cache write also covers the case where an existing object in the cache is modified. This occurs when:

A conditional request is made to the origin server and a

304 - Not Modifiedresponse is received.An alternate of the object is retrieved from an origin server and added to the object.

An alternate of the object is removed (e.g., due to a

DELETErequest).

In every case the metadata for the object must be modified. Because Traffic Server never

updates data already in the cache this means the first Doc will be written

to the cache again and the volume directory entry updated. Because a client

request has already been processed the first Doc has been read from cache

and is in memory. The alternate vector is updated as appropriate (an entry

added or removed, or changed to contain the new HTTP headers), and then written

to disk. It is possible for multiple alternates to be updated by different

CacheVC instances at the same time. The only contention is the first

Doc; the rest of the data for each alternate is completely independent.

Aggregation Buffer¶

Disk writes to cache are handled through an aggregation buffer. There is one

for each StripeSM instance. To minimize the number of system calls data

is written to disk in units of roughly target fragment size

bytes. The algorithm used is simple: data is piled up in the aggregation buffer

until no more will fit without going over the target fragment size, at which

point the buffer is written to disk and the volume directory entries for objects

with data in the buffer are updated with the actual disk locations for those

objects (which are determined by the write to disk action). After the buffer is

written it is cleared and process repeats. There is a special lookup table for

the aggregation buffer so that object lookup can find cache data in that memory.

Because data in the aggregation buffer is visible to other parts of the cache, particularly cache lookup, there is no need to push a partially filled aggregation buffer to disk. In effect, any such data is memory cached until enough additional cache content arrives to fill the buffer.

The target fragment size has little effect on small objects because the fragment

size is used only to parcel out disk write operations. For larger objects the

effect very significant as it causes those objects to be broken up in to

fragments at different locations on in the volume. Each fragment write has its

own entry in the volume directory which are computationally chained (each

cache key is computed from the previous one). If possible, a fragment

table is accumulated in the earliest Doc which has the offsets of the first

byte for each fragment.

Evacuation Mechanics¶

By default, the write cursor will overwrite (de facto evict from cache) objects

as it proceeds once it has gone around the cache stripe at least once.

In some cases this is not acceptable and the object is evacuated by reading

it from the cache and then writing it back to cache which moves the physical

storage of the object from in front of the write cursor to behind the write

cursor. Objects that are evacuated are handled in this way based on data in

stripe data structures (attached to the StripeSM instance).

Evacuation data structures are defined by dividing up the volume content into

a disjoint and contiguous set of regions of EVACUATION_BUCKET_SIZE bytes.

The PreservationTable::evacuate member is an array with an element for each

evacuation region. Each element is a doubly linked list of EvacuationBlock

instances. Each instance contains a Dir that specifies the fragment

to evacuate. It is assumed that an evacuation block is placed in the evacuation

bucket (array element) that corresponds to the evacuation region in which the

fragment is located although no ordering per bucket is enforced in the linked

list (this sorting is handled during evacuation). Objects are evacuated by

specifying the first or earliest fragment in the evacuation block. The

evacuation operation will then continue the evacuation for subsequent fragments

in the object by adding those fragments in evacuation blocks. Note that the

actual evacuation of those fragments is delayed until the write cursor reaches

the fragments, it is not necessarily done at the time the earliest fragment is

evacuated.

There are two types of evacuations: reader based and forced. The

EvacuationBlock has a reader count to track this. If the reader count is

zero, then it is a forced evacuation and the target, if it exists, will be

evacuated when the write cursor gets close. If the reader value is non-zero

then it is a count of entities that are currently expecting to be able to read

the object. Readers increment the count when they require read access to the

object, or create the EvacuationBlock with a count of 1. When a reader is

finished with the object it decrements the count and removes the EvacuationBlock

if the count goes to zero. If the EvacuationBlock already exists with a

count of zero, the count is not modified and the number of readers is not

tracked, so the evacuation is valid as long as the object exists.

Evacuation is driven by cache writes, essentially in StripeSM::aggWrite.

This method processes the pending cache virtual connections that are trying to

write to the stripe. Some of these may be evacuation virtual connections. If so

then the completion callback for that virtual connection is called as the data

is put in to the aggregation buffer.

When no more cache virtual connections can be processed (due to an empty queue

or the aggregation buffer filling) then StripeSM::evac_range is called

to clear the range to be overwritten plus an additional EVACUATION_SIZE

range. The buckets covering that range are checked. If there are any items in

the buckets a new cache virtual connection (a doc evacuator) is created and

used to read the evacuation item closest to the write cursor (i.e. with the

smallest offset in the stripe) instead of the aggregation write proceeding. When

the read completes it is checked for validity and if valid, the cache virtual

connection for it is placed at the front of the write queue for the stripe and

the write aggregation resumed.

Before doing a write, the method StripeSM::evac_range() is called to

start an evacuation. If any fragments are found in the buckets in the range the

earliest such fragment (smallest offset, closest to the write cursor) is

selected and read from disk and the aggregation buffer write is suspended. The

read is done via a cache virtual connection which also effectively serves as the

read buffer. Once the read is complete, that cache virtual connection instance

(the doc evacuator) is placed at the front of the stripe write queue and

written out in turn. Because the fragment data is now in memory it is acceptable

to overwrite the disk image.

Note that when normal stripe writing is resumed, this same check is done again, each time evaluating (if needed) a fragment and queuing them for writing in turn.

Updates to the directory are done when the write for the evacuated fragment completes. Multi-fragment objects are detected after the read completes for a fragment. If it is not the first fragment then the next fragment is marked for evacuation (which in turn, when it is read, will pull the subsequent fragment). The logic presumes that the end of the alternate is when the next key is not in the directory.

This interacts with the one at a time strategy of the aggregation write logic. If a fragment is close to the fragment being evacuated, it may end up in the same evacuation bucket. Because the aggregation write checks every time for the next fragment to evacuate it will find that next fragment and evacuate it before it is overwritten.

Evacuation Operation¶

The primary source of fragments to be evacuated are active fragments. That is, fragments which are currently open for reading or writing. This is tracked by the reader value in the evacuation blocks noted above.

If object pinning is enabled, then a scan is done on a regular basis as the write cursor moves to detect pinned objects and mark them for evacuation.

Fragments can also be evacuated through hit evacuation. This is configured by

proxy.config.cache.hit_evacuate_percent and

proxy.config.cache.hit_evacuate_size_limit. When a fragment is read it

is checked to see if it is close and in front of the write cursor, close being

less than the specified percent of the size of the stripe. If set at the default

value of 10, then if the fragment is within 10% of the size of the stripe, it

is marked for evacuation. This is cleared if the write cursor passes through the

fragment while it remains open (as all open objects are evacuated). If, when the

object is closed, the fragment is still marked then it is placed in the

appropriate evacuation bucket.

Footnotes